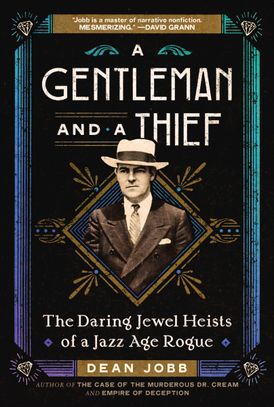

The robbing hood who stole from the rich and gave to himself: Dean Jobb’s A Gentleman and a Thief

Dean Jobb speaks about his new hit book, which is already a bestseller with the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star

ABT: You paint a complex picture of Arthur Barry, your A Gentleman and a Thief. In his “second story man” days, the people he robbed often described him as charming and polite – yet he frequently held them at gunpoint. His family today speak glowingly about him – yet knew never to ask him about his criminal past. What was your lasting impression of him after spending so much time in his worlds?

DJ: There was more good than bad in Arthur Barry. He was in trouble with the law as a youth, but risked his life to save others as a medic in the Great War. When he returned to New York City after the war, he was unable to find a job and decided to make his living from the least-violent crime he could think of – breaking into houses and stealing jewelry. While he sometimes carried a gun, he assured any homeowners he encountered during his burglaries that he did not want to hurt anyone; he only wanted their jewels. One socialite he robbed was impressed by how charming he was. And his victims, who ranged from a Rockefeller to Wall Street tycoons and heiresses, were rich enough to absorb the loss of expensive jewelry that was usually insured. He was no Robin Hood – he stole from the rich and gave to himself – but it’s hard at times not to root for him as he hoodwinks New York’s elite, crashing their parties, casing their mansions, and planning his next heist.

ABT: A Gentleman and a Thief is firmly set in the 1920s. The images of wild wealth contrasted with painful poverty and a world on edge seem … familiar. How would you compare his 1920s to our 2020s?

DJ: The aptly named Roaring Twenties was a time of obscene wealth, a yawning chasm between rich and poor, celebrity worship, press sensationalism, jarring technological and social change, rampant political corruption, and a looming day of reckoning – the stock market crash of 1929. In other words, as you note, it was a decade filled with shadows and echoes of our time.

ABT: Media coverage seems to have played a huge role in his career and fame. Some newspapers made his crimes seem like almost moral acts of a Robin Hood, while others falsely accused him of the most heinous of crimes (e.g. the Lindbergh kidnapping and killing) with little evidence. As a professor of journalism yourself, how would you assess the coverage of his life and crimes?

DJ: The press treated Barry and other audacious crooks of the era like rock stars. Their exploits were celebrated in front-page headlines and reporters scrambled for salacious details and exclusive interviews. Tabloid journalism came to America in this era – the New York Daily News, the country’s first newspaper modelled on the sensational, crime-obsessed papers of London’s Fleet Street – was founded in 1919. Despite the sensationalism, much of the coverage of Barry’s crimes was surprisingly accurate. Some of his exploits seem stranger than fiction, but that’s because they were.

ABT: Your books, including The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream, Empire of Deception, and Madness Mayhem and Murder, reveal a fascination with the dark side of life. What draws you into that world?

DJ: My university degrees are in history and when I got my start in journalism in the 1980s, I covered the legal beat as a reporter for the Halifax Chronicle Herald. These interests fused together and I began to research and write features about fascinating – and often forgotten – crime stories from Nova Scotia’s past. While I’m still drawn to local tales of murder and mayhem, my focus these days is in tracking down crimes and compelling characters wherever the stories take me, from Jazz Age New York and Chicago to Victorian-era London.

ABT: Why do you write about historic crooks? Have you considered any contemporary criminals as potential subjects for books?

DJ: I’m drawn to historical true crime because it offers a window on what the past was really like. Crimes put people and their times in the spotlight, with the vices and foibles and shortcomings of our ancestors on public display; they expose life as it was, stripped of the good-old-days nostalgia. Plus, crime stories are filled with drama – horrific acts, manhunts, trials, and the triumph – hopefully – of good over evil. I’ve covered many contemporary crimes as a journalist and an author, and for now at least I’m focused on historical crimes.

ABT: At times while reading A Gentleman and a Thief, I imagined you to be some sort of immortal reporter who covered the cases in the 1920s and wrote the book in the 2020s. What tips would you give to other writers on making history come alive on the page?

DJ: Read. Read everything you can about the time and place. Nonfiction writers are in the business of recreating lost worlds for readers and bringing the past to life in vivid detail. And that’s only possible if writers immerse themselves in the era they are writing about. The American popular historian David McCullough, author of John Adams, The Wright Brothers and other classic forays into history, described it as “marinating your head” – steeping yourself in what life was like for your characters. So read widely, research deeply, and use your findings sparingly, to avoid bogging down the narrative in excessive detail. And try to visit as many of the places where the events happened as possible.

Written By: