The lost bones and buildings of our ancestors

Black Harbour, Hidden Nova Scotia, and Archaeology and the Indigenous Peoples of the Maritimes

By Denise Flint

Who are we? Where did we come from? How did we get here?

Those are universal questions; we wouldn’t be human if we didn’t seek the answers. But sometimes those questions can be framed in such a way that the answers are exclusionary rather than opening up our knowledge about our existence. When we focus the question too narrowly, we may either ignore entire populations or dismiss their culture, virtually negating their existence.

We can know a people once existed, but know nothing about how they lived. We can stumble across abandoned buildings and know nothing about their purpose. We can even be ignorant of the fact that certain people existed in a particular space and time.

Three new books explore some of those previously darkened pathways, bringing to light a new narrative about our collective past that has been largely obscured. The books represent a kind of rediscovery of what came before us and they contain some surprises.

The first book is Black Harbour: Slavery and the Forgotten Histories of Black People in Newfoundland and Labrador, co-written by Xaiver Michael Campbell and Heather Barrett. Barrett is a white journalist whose ancestors have lived in Newfoundland for generations. Campbell is a Black man from Jamaica and a first-generation Newfoundlander. Their commonality? They both call the island in the middle of the North Atlantic home, and are deeply curious about its past.

One of the first things Campbell was told when he arrived in Newfoundland was that he wouldn’t see any faces that looked like his. That turned out not to be true, but it did start him wondering about the entrenched idea that there are no Black people in Newfoundland and there never have been. After all, there were Black people in every other British colony around the world. Why would Newfoundland be different?

It wasn’t. During the course of their research, Campbell and Barrett discovered references to Black slaves and Black sailors with connections to Newfoundland, as well as Newfoundland’s connection to the wider slave trade that was deemed essential to the development of European economic and trade systems. But that story has never been part of popular history.

“It’s important to acknowledge the bad parts of our history as well as the good,” says Barrett. “And to document and give recognition to the people from all backgrounds who helped build life in Newfoundland and Labrador over the centuries. That heritage belongs to all of us.”

“By telling these stories we hope to add to the history of Newfoundland,” Campbell says. “These people were taken away from their own places and their own people and taken into bondage. It’s really important to highlight the stories that have been largely forgotten whenever we can. There’s a lot of historical erasure going on everywhere. When the rich, white men were deciding things, there were a lot of other people in the room.”

Barrett says being in the same room as Campbell as they created Black Harbour was an enriching experience. “I now know that not everyone in Newfoundland was from an English or Irish background like me. Newfoundland is a more complex, rich, and interesting place and society than we may have thought.”

To call Archaeology and the Indigenous Peoples of the Maritimes by Michael Deal comprehensive seems almost trite – there are a full 62 pages devoted to references alone. Deal is a retired professor who taught in the faculty of archaeology at Memorial University of Newfoundland. His work focussed on the ancient archaeology of the land now known as the Maritime provinces and the book is an extensive study that grew out of Deal’s lectures and online notes dating back to 2000.

One thing he acknowledges is how much the study of archaeology has changed since he began nearly 40 years ago. One of those changes is the contribution of an Indigenous perspective to our understanding of the past.

Speaking of the European tradition he says, “We can’t go back in time, so we are basing our understanding on what was left behind: the artefacts, the plant remains, the animal bones, even the residue on pots. We look at it linearly and we try to create a narrative of history and identify events or changes. What we’ll never know is what they were thinking and just how complex their religion and social organizations and politics were. We look for triggers that caused changes and set up a timeline with developmental periods.”

But that’s not the only way to gain an understanding of the past. Speaking of Indigenous people Deal, who is white, says, “They think about history in a different way than we do, based on oral traditions and community values.” He uses Indigenous tales about the retreat of the glaciers or the forming of the Minas Basin as examples. “Their ancestors were there and recorded these things in oral history and it’s something we recognize as well and so the two forms converge.”

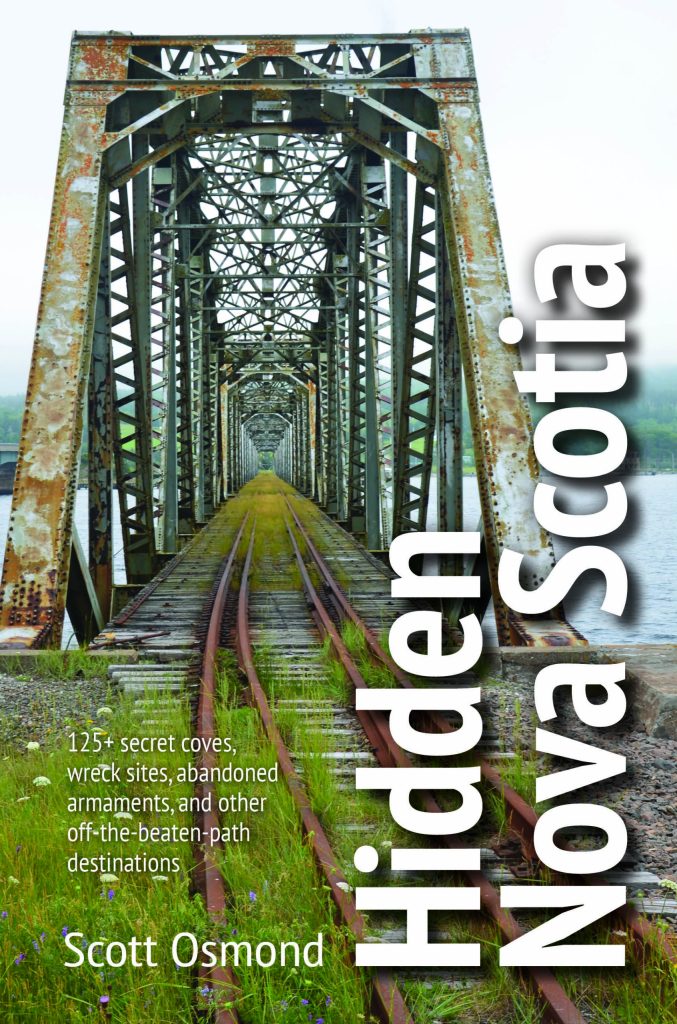

Another type of vanishing history comes from Hidden Nova Scotia by Scott Osmond, which bills itself as “your guide to 125+ secret coves, wreck sites, abandoned armaments, and other off-the-beaten-path destinations.” Divided by regions, the book tells you exactly how and were to find quirky and compelling places of interest across the province.

Want to see a piece of the Berlin Wall? Look behind Dalhousie’s agricultural campus in Bible Hill. An Royal Canadian Air Force radar site? Climb a barren hill overlooking Cole Harbour. At first it sounds fairly straightforward, but even a cursory glance through the pages shows that this is more than a simple guide.

Osmond prefers to think of it as an atlas of curious wonders. “A lot of times these stories aren’t known. When you dig a little deeper, their deeper significance is found. For example, the World War II and Cold War things that are buried around the province show the fear and the effort as we all came together to build this infrastructure.

“Some of these things are in the middle of nowhere, but here they are. They used to be a town or a mine. Old lumber mills have hired a lot of people. Either you or your neighbour has a connection to this industry. They show our impact on the land and how far our reach is.”

Hidden Nova Scotia is an activity guide meant to lead you to some of the lesser known features, both natural and built, of the province. But is also a guide to the history, culture and impact of the people who have inhabited the province.

These three volumes, with their study of Black connections to Newfoundland, Indigenous heritage in the Maritimes and the obscure artefacts of the modern world, bring to us largely forgotten or even unknown parts of a heritage that belongs to us all. And, as Barrett says, that makes for a more complex, rich and interesting society.

Denise Flint is an award-winning freelance writer and editor with years of experience writing on a diversity of subjects for a wide audience.

Written By: