Food from the refugees of the ‘Shams Élysées’ and mitji in Mi’kmaki

Food writer Gabby Peyton reviews Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World’s Largest Syrian Refugee Camp and Mitji—Let’s Eat!: Mi’kmaq Recipes from Sikniktuk

The movement of food, or the globalization of cuisines, has occurred for centuries. As long as the migration of people has existed — whether for political, socioeconomic or colonial reasons — their cuisines have come along with them. Without it, we wouldn’t have the French-infused Bahn Mi in Vietnam created by the mingling of French colonial culinary culture and Vietnamese herbaceous ingredients, nor the Montreal smoked meat sandwich here in Canada due to the influx of Jewish immigrants in the mid-20th century, an interesting evolution of cuisines by necessity.

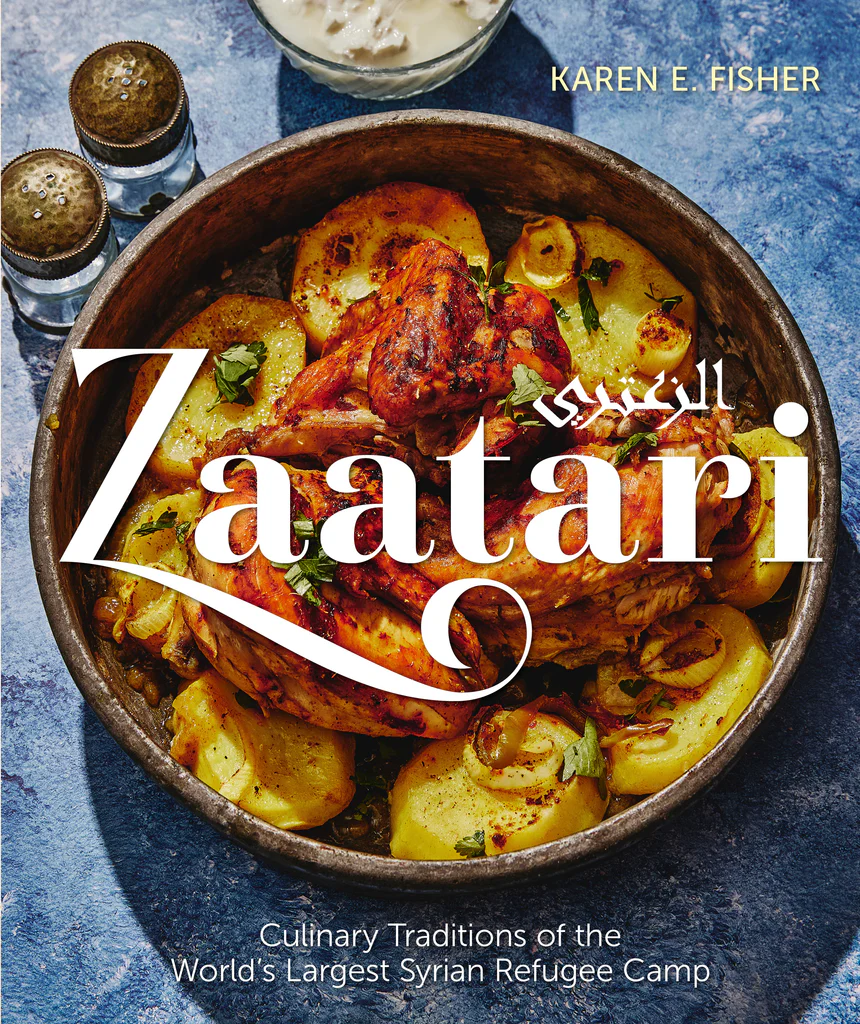

But, as Karen E. Fisher highlights in her new cookbook, Zaatari: Culinary Traditions of the World’s Largest Syrian Refugee Camp, the movement of Syrian refugees, while forced, has united Syrian cuisine and fortified its cultural heritage. Fisher created the cookbook in collaboration with more than 2,000 refugees displaced by the Syrian civil war who live and cook in Zaatari, a 1,300-acre refugee camp in Jordan.

However, Zaatari is not just a cookbook — it is an ethnographic study, a celebration of culinary culture and a story of resilience. Fisher is a field ethnographer from St. John’s, N.L., but now splits her time between Seattle, where she is a professor of information science at the University of Washington, and the Zaatari camp near the Jordanian-Syrian border. She first went to the camp in 2015 with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as a field researcher looking at internet usage and library tools, but soon realized the importance of documenting the cuisine, as she states in the introduction: “My red notebook — fat with stories, lore and wisdom — smells like Zaatari.”

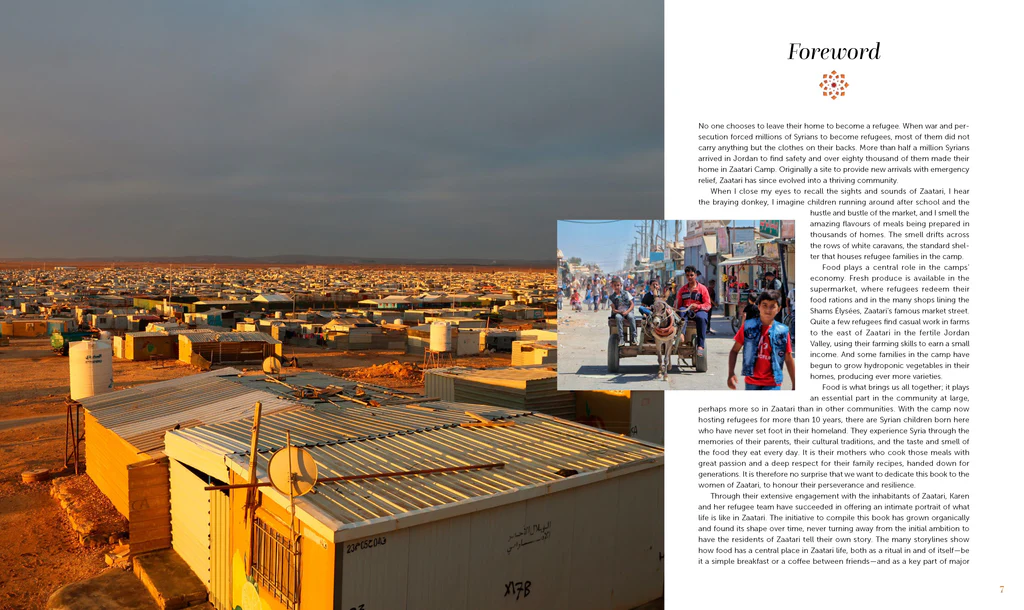

The refugee camp was established in July 2012 as Syrians fled the start of the civil war to neighbouring Jordan. Within a year more than 120,000 refugees were living in the camp, which sits about an hour’s drive from Amman, and over the past decade, the encampment first housing refugees in tents has grown into the largest refugee camp in the Middle East and one of the largest refugee camps in the world. There are now 83,000 displaced Syrians living in Zaatari, which has roads lined with caravans throughout 12 districts with schools, libraries and hospitals. Zaatari street-food stands and souks sell crispy falafel and spices along the original market street, known as Shams Élysées, which is a play on the word ash-Sham, which Syrians call Damascus, and the renowned Parisian boulevard the Champs-Élysées.

Refugee camps are thought to be transitional, filled with transient lost citizens trying to find their way to a better life. However, many people have spent years there and many children born there (more than 20,000 according to the UNHCR) have never been to Syria, but as Fisher says, “they experience Syria through the memories of their parents, their cultural traditions, and the taste and smell of the food they eat every day.”

Zaatari is named after zaatar, the Arabic word for thyme which is a favourite spice blend throughout the Middle East made with thyme, sesame seeds, oregano, marjoram, salt and sometimes sumac — a name which seems fitting considering the tremendous effort at Zaatari to maintain and celebrate Syrian culinary heritage.

The table of contents is the first hint that Zaatari is not a conventional cookbook. This book goes against many of the typical cookbook conventions, at least in the North American sense — the chapters are not divided by appetizers, mains or desserts, but instead, it tells stories through the meals of the day, celebration dishes and Zaatari pantry staples interwoven with stories, poems (both written in English and Arabic) and drawings.

An essential section on Arabic coffee comes after the Syrian welcome where the reader learns about the two types of coffee (qahwa) on offer at Zaatari — the slowly-prepared Arabic coffee, cardamom flavoured and watery compared to the dark, quickly prepared (and consumed) Turkish coffee — and traditionally served with dates (tamur).

Recipes for ftoor, breakfast, come next. There’s hummus (a recipe which Fisher recounts was almost overlooked in the recipe picking process), muhammara and a recipe for jazmaz, which is widely known outside of Zaatari and greater Syria by its Palestinian name shakshuka.

Heartening stories, poems and drawings about the libraries, the TIGER girls and oil painters are interspersed with recipes for fattoush, bamya and of course breads of all kinds before the “Meet You at the Shams Élysées” chapter where Fisher showcases some of the 3,000 micro-businesses in Zaatari. Its street vendors serve falafel, shish tawook and booza, the Middle East’s version of ice cream (and a better version in my opinion) flavoured with flower blossom water and vanilla.

A section on ghada, lunch, the most important and largest meal of the day, is followed by chapters on Ramadan with an array of drink recipes, Zaatari wedding dishes and meals for new mothers. The final chapters take on a more traditional structure entitled “Breads, Sweets, and Drinks,” “The Zaatari Pantry” filled with spice blends, and “Jams and Pickles.”

The recipes in Zaatari are written straightforwardly with easy instructions and most ingredients should be available at most grocery stores, if not a specialty Middle Eastern store. In the introduction, Fisher explains that more than 2,000 people, mostly women, workshopped to narrow down the recipes included, which have been modified to feed four to six people. The process of creating the recipes for the cookbook was challenging — no one is taking a cookbook with them when fleeing, and many of the women cooked for large groups, measuring with their hearts, a well-rehearsed dance they have done for generations — “using not measuring spoons, but rather their eyes and hands, while jar lids, coffee cups, and glasses become quantifiers and qualifiers.”

Flipping through the pages of the book is like wandering the dusty streets of Zaatari. I can almost hear the hawkers selling their wares before ghada, smell the sweet cardamom coffee bubbling on the stove and feel the heat of the desert sun. The photography, a collection of images documenting daily eating, cooking and living taken by residents of the camp and the UNCHR, is colourful and poignant while the food photography, mostly by Alex Lau with Jason LeCras, is mouth-wateringly vivid showing delicious food styled with some of the dishes and serving ware Fisher collected across Jordan.

Cookbooks are always political, inadvertently connected to the people who create them and the places from which they draw inspiration. Zaatari is even more so. Cooking the recipes from this book will both delight the reader-cook but also evoke a deeper conversation about the Syrian war, the world around us and the movement of food. Zaatari is for anyone who wants a focused look into the world’s largest Syrian refugee camp which emanates a sense of community, a sense of identity and a sense of understanding that food unites us all.

Let’s Eat in Mi’kmaki

The call to dinner is appreciated the world over; everyone is eager to sit down together and eat. In Mi’kmaw, the call is “mitji”, which translates to “let’s eat”, and it’s a fitting title for the new cookbook Mitji—Let’s Eat!: Mi’kmaq Recipes from Sikniktuk by Margaret Augustine and Lauren Beck showcasing Mi’kmaq recipes, stories and traditions which have been passed down through the generations by ancestors and Elders.

The wisdom and tradition in Mitji are collected from Sikniktuk, one of the seven traditional districts that make up the Elsipogtog First Nation, and it’s clear from the first few pages how in-depth the research is — which shouldn’t be surprising considering both Augustine and Beck are academics. Augustine is an assistant professor at the University of Prince Edward Island and is married to Dr. Patrick Augustine, an Elder of the Elsipogtog First Nation and professor at UPEI specializing in Maritimes treaty negotiations. Beck is a professor in the modern languages department at Mount Allison University and is married to Rob LeBlanc, who teaches in the Aotiitj programme at Elsipogtog First Nation. Augustine and Beck had a large group of contributors who helped to give and transcribe dozens of interviews and translate documents, while others donated serving ware and dishes for the photography.

Those images were taken by Patricia Bourque, a member of the Lennox Island First Nation on Epekwitk/Prince Edward Island.

The recipes of Mitji are organized by season, which determines how the Mi’kmaw cook and eat, with the fifth section highlighting recipes enjoyed all year round. Spring’s chapter starts with a gorgeous image of ma’susi (fiddleheads) and showcases recipes of in-season ingredients like eel stew and multiple recipes featuring jigaw (striped bass). Into the summer Mitji presents multiple recipes for local berries, lobster and salmon, including Anita Joseph’s recipe for nijinjk (salmon roe) baked low and slow with butter and onions. Potatoes, apples and moose dominate the fall chapter and there are great explainers on preserving techniques, while the winter season is filled with soup recipes and rabbit stews.

Each recipe is preceded by context, whether that be biographical information of the contributor, or background on the origins of the dish, helping any cook to understand the impact of colonization on Mi’kmaw cooking and life.

There are also great tidbits of information, historical images and stories sprinkled throughout the pages making Mitji a fun read with unexpected (but appreciated) spoonfuls of knowledge. The recipes themselves are simply written, with ingredients that any East Coast cook could find and enjoy — when they’re in season of course.

Mitji is not only a great cookbook for anyone interested in learning about Mi’kmaw cuisine, but also packs a wealth of knowledge about the great culture, contextualization for the Elsipogtog First Nation and a delicious way to learn new cooking methods.

Gabby Peyton is a food and travel writer based in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, obsessed with cheese, historical fiction and planning her next trip — to eat.

Her work on travel, food and culinary history has appeared in Canadian Geographic, The Globe and Mail, EnRoute Magazine, Chatelaine, CBC and Eater. Gabby’s first book Where We Ate: A Field Guide to Canada’s Restaurants, Past and Present was published in 2023 and became a bestseller — you can purchase it wherever you buy books.

Written By: