Books by Heart: Len & Cub’s lost love story, found in photos

Books by Heart is a new initiative to help humanize Nova Scotia hospital care, with a curated collection of ebooks and audiobooks available for free to patients, families, and staff. The reading platform and program are being tested out first at the University of King’s College, and we’ve enlisted some King’s student reviewers to help promote more engagement with the collection within the King’s community. Find out more about the project (and read this book for free if you’re a member of the King’s community!) at BooksByHeartKings.ca

Review by Anya Deady

I remember hearing as a kid this oft-quoted, yet unauthored, mantra that went something like this: “If you really want to know what someone cares about, pay attention to what they photograph.” To me, the claim remains overly sentimental, but if I did not yet feel like this was a true — or at least honorable — idea, the composition of Dusty Green and Meredith J. Batt’s Len & Cub: A Queer History has confirmed it. At once a powerful re-centering of the archive and a sentimental look at the idea that we have always been here, this book is as dedicated to shining light on historical fact as it is to re-imagining the ways in which we treat queer love as time goes on.

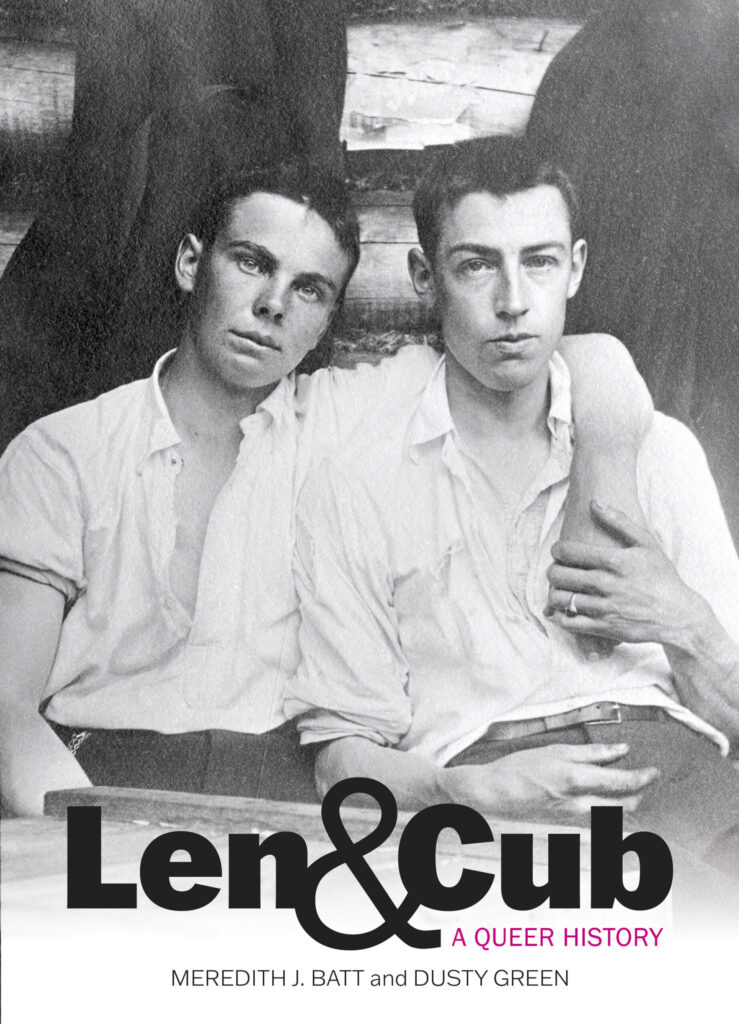

Len & Cub tells the long — but too short — coming-of-age story of boyfriends Leonard Olive Keith (1891-1950) and Joseph Austin Coates (1899-1965), known in town as Len and Cub. The town in question is Havelock, New Brunswick, known to them at the time as Butternut Ridge. Interspersed with affectionate photographs taken on Len’s Kodak, “their story remains arguably the oldest known photographic record of a same-sex couple in New Brunswick or in the Maritimes.”

Part of the magic of this book lies in how it draws out a story that has been, for all intents and purposes, lost to time. While the authors emphasize that there are no written accounts of the love that the pair shared, like love letters, “The photos of Len and Cub in this book show a poignant love, whatever the language they would have used to describe it.” Len’s photographs have remained in the archive for some time, but Len & Cub is first to consider them at any length through a queer lens, letting the photographs speak for themselves while arming their readers with historical specificity, context, and above all, wonder.

Green and Batt outline the boyfriends’ affections from boyhood to adulthood, telling you about “[their] boys” and reading between the lines without being purely speculative. This book reads as if you are sat on an old but comfortable couch, grazing through a photo album with a friend who fills in the blanks for you. As you flip through, there’s a reminiscent eye uncovering key details, a thumb smudging up the edges of the photographs, a voice pointing out the importance of Len’s Ford truck, telling you about how it allowed him alone time with Cub. The authors remind us of the wonder of looking through photo collections: firsthand testimony may be lost to time, but photography, as an art, leaves little trails behind for us. And when we see them years later, we’re reminded why we take them in the first place.

Hatred ends a love story

Green and Batt draw Len and Cub’s story out of the photographs and delicately place it next to contemporary conceptions of queerness while dissecting the time-specific backdrops of Len and Cub’s time: impending wars, Prohibition, changing attitudes towards human sexuality, and the boom of photographic technology led by Kodak. But most importantly, Green and Batt tell us, Len and Cub’s story provides “a clear and permanent record of a queer relationship existing despite the hostile time and environment in which the couple lived,” an environment that eventually outed Len and led to him fleeing the town, perhaps never to have the same relationship with Cub again.

Something that emerges through Len’s photographs is familiar to any queer photographer: the photos reflect the sentimental attempt to escape the eyes of others while trying to find a sense of safety and joy in being seen. As a reader and viewer of this book, you can feel the love. While the frequent picturing of Cub in photos around 1914 “may not be remarkable in itself,” the “poses and demeanour are undeniably intimate. Photos from this period show them at their most affectionate: holding hands, wrapping their arms around each other, or lying together either in a cabin bed or outdoors in the meadows surrounding Havelock.”

Green and Batt lay bare the ways in which Len and Cub’s queerness operated in their rural, increasingly suffocating atmosphere of the early 20th century. Any readers of works from the Beat Generation — Jack Kerouac’s On the Road or Allen Ginsberg’s Howl — might find in Len & Cub a closer-to-home portrait of queer love, the rise of the automobile, and the rise of amateur photography amidst a culture of war and heteronormativity.

A quick read and a deeply moving portrait of queer affection, Len & Cub is vital for anyone interested in the history of queerness in Canada, queer photography, or Eastern Canadian history in general. As one of the dedications reads: “For the queer youth of New Brunswick, may you take heart from this story and find your place in this province.”

Part of the Books By Heart at King’s collection, Len & Cub is available as an ebook for free for anyone affiliated with the University of King’s College until August 2023. And, once you finish Len & Cub in one sitting (like I did), you’ll also find other queer non-fiction reads in the collection: Low Road Forever: Essays by Tara Thorne, a look at pop culture, queerness, and feminism in the contemporary moment, and Before the Parade by Rebecca Rose for a history of the queer community in Halifax.

Written By: