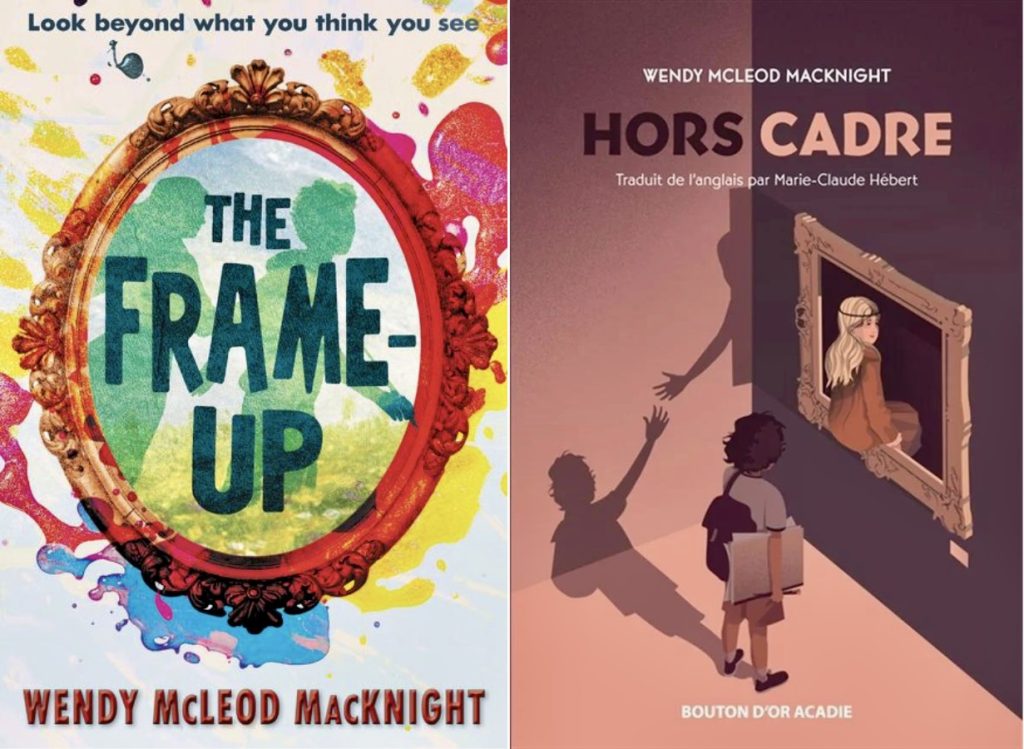

Found in translation: How ‘The Frame-up’ became ‘Hors cadre,’ an art-gallery novel in two tongues

By Marie-Claude Hebert

I had worked with the Beaverbrook Art Gallery for years when The Frame-Up by Wendy McLeod MacKnight was released. I read it and was charmed by the story of a boy discovering that the paintings are alive in the iconic New Brunswick gallery.

The gallery had created a guided tour based on the book’s characters: the subjects of the paintings themselves, which I also got to translate. This brought me even closer to the characters, as the tour was narrated by Mona Dunn, the main painted protagonist of the book, and I just knew I had to translate it.

Once publishers Bouton d’or Acadie and Greenwillow Books had worked out the details, I set out on this beautiful and complex adventure.

The most interesting and challenging aspect of translating The Frame-Up into Hors cadre was the wide variety of voices. The thing is, many of the characters are paintings by different artists from different eras, so each person needed to be researched individually. Then came time to figure out how they would speak to each other.

Mona Dunn, for example, was painted in 1915 by William Orpen, a British artist. She was a 12-year-old girl from a very prominent family, portrayed in her everyday dress on a dark-broody background. Her personality, though, was feisty and very empathetic. How would she have spoken back then? How would she address Lord Beaverbrook who, though imposing and overbearing to most everyone (in real life and in the book), was a close family friend to Mona? Should she use the polite “vous”? Or be more informal with him and address him with “tu”?

Then, there were her interactions with kids her age inside and outside of the frame. They should be more informal, that was clear. Though her dear friend Clem Cotterell was painted in 1658, he strove to speak the current day lingo, and Sargent Singer, living in today’s world, would also communicate with Mona using today’s syntax and wording.

Madame Juliette, portrayed in Madame Juliette dans le jardin by Impressionist Eugène Boudin, was painted in 1895, in turn-of-the-century France. While her fiancé, Lieutenant-Colonel Edmund Nugent, represented in a massive piece by Thomas Gainsborough, was painted more than a century earlier, in 1764. He was a very proper Englishman. They were both high society, but from different eras, different cultures and different realities.

Le vernaculaire Québécois

In contrast, the characters living in The White Horse Inn, are of another ilk. And even within that frame, there is a variety of people from a wide array of backgrounds. Bertha and Argyle Smith were particularly fun to adapt, and I happily delved into an old Québécois vernacular.

This exercise in voice was a massive undertaking and I consulted an editor friend, other translators as well as my partner. Our copy editor and I went back and forth for consistency in terms of speech choices for example, and in the end, all these colourful characters managed to endear themselves to me and, hopefully, to the reader.

Another wonderful challenge I took on with gusto was the humour McLeod MacKnight sprinkled generously into this book. Santiago El Grande, Salvador Dali’s enormous horse and rider, are quite hoity-toity and bossy, but really, they just want to have a purpose and people to talk to, like anyone else. Mona and the horse engage in some beautiful repartee that I quite enjoyed adapting into French.

Found in translation

And this is what a translation really is: an adaptation of the original text for the target audience. Expressions and maxims don’t always have their equivalent in French, and if they do, some words in the equivalent make it impossible to use in the same place. This is where I play with the text. Sometimes humour shows up somewhere else, a wordplay can come in handy and sound much more natural in another dialogue or setting, and an old-timey word or phrase can drive a character’s provenance and class home in a different act.

All in all, translating The Frame-Up was a gorgeous delight. And, as is the case with all good books, I was sad to leave our characters behind after my last read through, but ever so excited to be able to read the aloud, thus bringing them to life during events like the Frye Festival in April, the launch at the gallery in Fredericton in late winter, and the upcoming Salon du livre de Dieppe this October.

Marie-Claude Hébert is a certified translator, educator and textile artist. She has been interested in the environment and textiles since she was a child, and she is blessed to marry her specialties and passions by working with the GDDPC on natural dyes. Marie-Claude chose to settle in Cocagne, N.B., with her partner and children to be part of this committed and open community. It is with the greatest pleasure that she works and teaches with natural dyes and translates children’s books.

Written By: