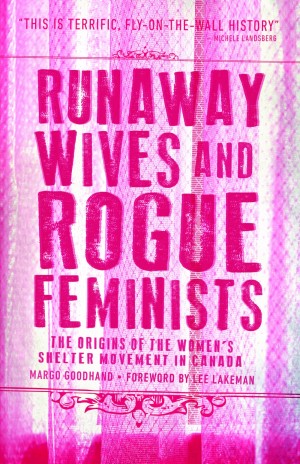

Books By Heart: Runaway Wives and Rogue Feminists

Review of Runaway Wives and Rogue Feminists by Margo Goodhand

Books by Heart is a new initiative to help humanize Nova Scotia hospital care, with a curated collection of ebooks and audiobooks available for free to patients, families, and staff. The reading platform and program are being tested out first at the University of King’s College, and we’ve enlisted some King’s student reviewers to help promote more engagement with the collection within the King’s community. Find out more about the project (and read this book for free if you’re a member of the King’s community!) at BooksByHeartKings.ca

I picked up Margo Goodhand’s Runaway Wives and Rogue Feminists: The Origins of the Women’s Shelter Movement in Canada thinking that it was likely to be an enlightening read. I was thinking that it might tell me a thing or two I already knew on some level, but I was excited by the possibility that it might illuminate these things against a particular backdrop of which I was previously unaware. All of this was an understatement.

A galvanizing read and a remarkable confirmation of that sinking feeling in your stomach, Runaway Wives and Rogue Feminists tells the stories of the pioneering Canadian women who fought to carve out safe spaces for other women facing violence, poverty, and uncertainty from the 1960s onwards. But it doesn’t stop there. “May [the book] also,” Goodhand writes, “reignite debate on a war we have yet to win – the war on women.” That is, Goodhand makes us ask ourselves: how far have we really come?

From Aldergrove to Edmonton to Saskatoon to Toronto to Vancouver, Goodhand outlines the ways in which the women’s shelter movement seemed to (remarkably) emerge in specific locales across Canada simultaneously, arising out of a historical air as if this kind of revolt was simply built into the fabric of being a woman at the time.

Reflecting on the Toronto Interval House being the first battered women’s shelter in Canada, one of the founders, Lynn Zimmer, describes the simultaneous formation of these shelters in dramatic terms. “Let’s just say it was a spontaneous combustion thing and it just spread like wildfire. Because in our way, we each were first, we didn’t copy each other, we just did it. We had no idea how revolutionary it was.” Goodhand refers to this idea as an “awakening, of sorts, combined with the right social climate.”

But carving out these spaces certainly was not easy work, and the road had yet to be paved. As B.C. feminist Jillian Ridington puts it, quoted by Goodhand, “Battered wives had few resources to turn to: because no one dealt with the problem, no one kept statistics. Because no statistics on incidents were available, it was not recognized as a problem. Catch 22.” Goodhand’s focus, violence against women and ongoing gender disparity, has a kind of gravitational pull in two directions.

One the one hand, Goodhand does not shy away from the truth of the matter: that the stories of these women who came to these shelters were frequently fraught with horrific and nearly unspeakable violence. On the other, Goodhand allows us some degree of hope in our collective ability to work together and fight back: in the first place, the women’s shelter movement arose out of a non-hierarchical, inventive, and collectively caring dynamic. As Billie Stone puts it, “We were all at the same level; there was no holier-than-thou kind of thing, just women helping women. But we did it.”

While acknowledging the harm that women have endured, Goodhand also makes it clear that hope has not run out, though the fight has yet to be won.

The women in this book shine with their dedication, care, intuition, and brilliance. With these women’s stories, Goodhand draws the conclusion that, “At the heart of every one of the practical, passionate women who got involved in this small slice of Canadian history is the same sense of justice, courage and quiet outrage. If we learn anything from their legacy, it’s that more of us need to share their outrage and their courage. We stand on their shoulders.”

From Goodhand’s candidness with the state of feminism, to her ability to bring to life the stories of women across generations, provinces, and life experience, and finally to her dedication to the historical complexity of an overlooked but undeniably vital period in Canada’s history: all of this makes this book utterly incendiary. It is, in the end, a call to action: more of us need to share their outrage and their courage. I’ll remember that line for a long time.

But, above all, the fight must continue to follow what Rosemary Brown spoke about decades ago: “Unless the women’s liberation movement identifies with and looks into the liberation movement of all oppressed groups, it will never achieve its goals. Unless it identifies with and supports the struggle of the poor, of oppressed races, of the old and of other disadvantaged groups in society, it will never achieve its goals. Because not to do so would be to isolate itself from the masses of women, since women make up a large segment of all of these groups.”

I’m calling this book required reading, along with Nora Loreto’s Take Back the Fight; Robyn Maynard’s Policing Black Lives; and Arthur Manuel and Grand Chief Ronald Derrickson’s The Reconciliation Manifesto. You can find all of these vital e-books in the Books By Heart Collection at King’s, available for free, all summer long, for members of the King’s community!

Written By: